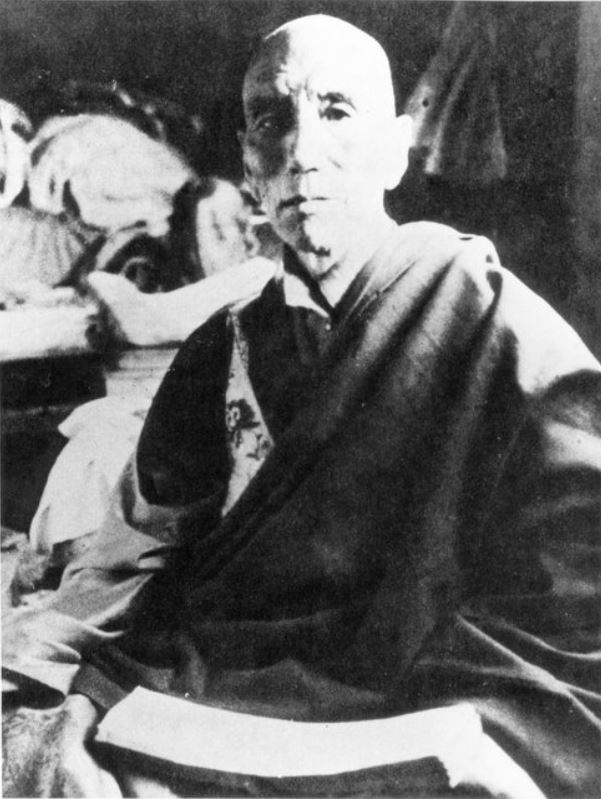

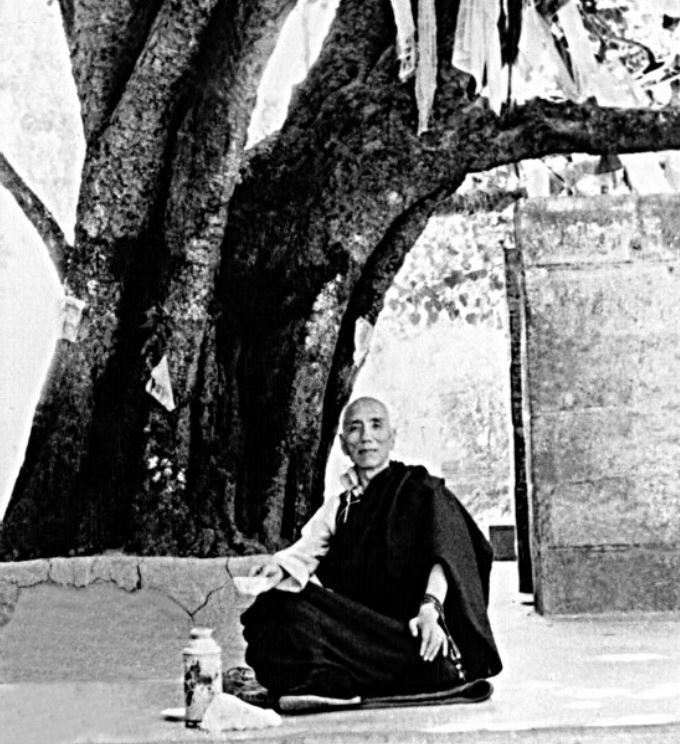

Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro,(1893-1959) was the last of the great masters to live almost his entire lifetime in Tibet where his extraordinary activity could flourish unimpeded by Modern Times. This account of his life propels us into Planet Tibet: the good, the bad and the inconceivable.

He was so humble he travelled like a beggar with neither entourage nor baggage while on pilgrimage; but so ferocious a disciplinarian he would order 500 strokes of the lash for monks’ misbehaviour – and watch the punishment through his window. At his monastery, he was feared like Yama, the Lord of Death. He was also a great collector of precious and somewhat exotic blessing substances. In his later life on pilgrimage, he crept at night into the kudung* of Terton Orgyen Lingpa, cut off a bit of flesh and ate some, keeping the remainder to distribute in blessing pills. It was said that rainbow coloured lights were seen to dissolve into it. He also took a large quantity of bones from the sacred body of Sangye Lingpa. At another monastery he encouraged some monks to scale up a wall and pluck a few hairs from the hanging head of a heretic , Trokje Gawo which he needed in order to avert heretic sorcery. He kept the unwashed handkerchief of Adzom Drukpa and put the dried up mucous into his mouth when he was ill. There were no boundaries to his enlightened, and unconventional, behaviour.

On a pilgrimage to Lhasa he was asked to do a divination about the future security of Tibet. Following the outcome of the divination, he ordered a one storey high statue of Guru Nangsi Zilnon (a wrathful aspect of Guru Rinpoche) facing China to be built at the Tsuglakhang Temple surrounded by four stupas. In spite of the 13th Dalai Lama’s command to the Tibetan Government to build the image exactly as Chokyi Lodro had instructed, they constructed a small Indian style image of Guru Rinpoche facing India and didn’t bother to add the four stupas. They blundered, typically, because of sectarian bias. ”Ceremonies to avert misfortune do not help if they are not accomplished at the right time”, Jamyang Khyentse commented. Their behaviour, he added, was catastrophically misjudged. And with that, Planet Tibet disappeared.

And then was born Modern Times. In one prophetic dream Chokyi Lodro met the prince of Derge and had a vision that the prince was beating a row of people, among them Lakar Sogyal, later known as Sogyal Rinpoche. ”The prince was quite mad! He then lay on his back naked, and said ”the boy might go crazy and cause internal strife.”

* — Kundung: the sacred body of one who has attained enlightenment and therefore it has not decomposed.

Known as the master of masters, Chokyi Lodro was indisputably the greatest spiritual hero of the last century. A renowned Rime scholar and practitioner, he promulgated all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, giving teachings, empowerments and detailed instructions to both humblest and greatest who sought his guidance. Among the great masters to whom he bestowed or exchanged empowerments and from whom he both gave and received teachings were the Sakya Trizin, the Sakya Dagchen Rinpoche, the 16th Karmapa, Dilgo Khyentse, the Dodrupchen, Adzom Drukpa and the Dalai Lama. The list of his renowned students includes Namkhai Norbu, Tarthang Tulku, Chagyud Tulku and Chogyam Trungpa. His masters were Loter Wangpo, Dodrupchen, Adzom Drukpa, Chokyi Lodro’s own father and Chatral Rinpoche.

He staunchly upheld the monastic vows of the Vinaya right up until the age of 56, when he became very ill, and following the divination of Palpung Situ to take a consort to prolong his life, became a Heruka. A 16 year old dakini, Tsering Chodron, a daughter of the prominent Lakar family, who were sponsors of his monastery, had already offered herself to him. However he never forgot Padmasambhava’s instruction: though your view be as vast as the sky let your conduct be as fine as barley flour. He was also a terton – the reincarnation not only of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo but of King Trisong Detsen – and a buddha.

To understand deeply what a buddha is, requires the mind of a buddha, but to explain it in words invites a virtual verbal explosion. His accomplishments fill 539 pages of an unusual combination of biography cum hagiography. The Life is both a compendium of supreme accomplishments and a manual of enlightenment to be contemplated. The list of all the transmissions he received takes up three volumes (only partially reproduced here). If we add to that a list of the shedras and retreat centres he established, the statues, thankas and stupas he created, the books printed, the time spent in retreat, his visions and prophecies – which alone are a separate large volume (he received no less than 17 visions of Longchen Rabjam) – we have the life of a superhuman being in which every second was used for the dharma. It’s inspiring but daunting to contemplate the mountain of merit required to become a buddha.

This weighty volume boasts a Foreword by Chokyi Lodro’s activity reincarnation Dzongsar Khyentse, a rambling two hundred and fifty page anecdotal oral history by Orgyen Tobgyal, son of the third Neten Chokling, before raising the curtain on the exalting hagiography by the great Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. To unravel the most important relationship of the book – that of author and subject – requires us to understand another inconceivable: Khyentse Wangpo, the original 19th century Rime master, manifested in several reincarnations. Dilgo Khyentse was both the mind reincarnation and also the devoted attendant of Chokyi Lodro, another reincarnation of Khyentse Wangpo and the subject of this book. So both the author and the subject of this biography were once one and the same.

If you have to stop and contemplate this, it could be a good sign. It could explain why Dzongsar Khyentse says in his Foreword, it is actually possible to read this namthar and attain enlightenment. The namthar stands as a unique manual of how to attain unfathomable buddhahood, step by meticulous step from the vinaya, to the mahayana, and the vajrayana without skipping any of the basics to get to the higher tantric and Dzogchen teachings.

But it is not an easy read. I have to admit it took several months to get through the book. The sheer number of inter-related masters who are embedded, sometimes as devotees, sometimes as teachers, sometimes as family , is like a cast of thousands in a fast moving film. Some have walk- on parts, some stay longer and play feature roles. Raking through it is like tilling volcanic soil with a trowel. The prose style in Tibetan of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche is said to be sublime. Like it or not, the book cannot be judged on its literary merit which does not always percolate through in translation. On the other hand, the meritorious activity of those who wrote, translated and brought the book to fruition, is so great that no Buddhist would dare to review it using the standards of modern criticism.

The oral history, as remembered by OrgenTobgyal, leads us gently through the humanised part of the biography before we have to face the Compendium of Lists. Apparently, his contribution was an add-on to the translation, starting quite dramatically when one winter Dzongsar Khyentse parked himself on his sofa and refused to move until he divulged all he could remember about Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro. Two hundred and fifty pages later we have a more or less incomplete picture, but it is really all we need to know. And the real namthar hasn’t even begun.

By that time we have either fallen under its spell and continued to page 539, stopped reading, or relegated it to a sacred place on the book shelf believing it to be a milestone in Tibetan biographic literature. ”Chokyi Lodro loved the dharma from the depths of his heart,” comments Dilgo Khyentse. Two sublime beings. One mind. Multiple dimensions.

Norma (Naomi) Levine is the author of 5 titles on Buddhist themes:

Thanks Naomi. Reviewing this vast hagiographic namthar and the associated bio from Orgyen Tobgyal must have been hard indeed. Planet Tibet is right. You’ve slightly lifted a veil – not sure that what’s under it is so delightful.